Frankye Myers: From Riverside Health, this is the Healthy You Podcast where we talk about a range of health-related topics focused on improving your physical and mental health. We chat with our providers, team members, patients, and caregivers to learn more about how to maintain a healthy lifestyle and improve overall physical and mental health.

So, let's dive in to learn more about becoming a healthier you.

I am Frankye Myers, system Chief Nursing Officer for Riverside Health, and I'm really excited to have Dr. William McAllister, who is a neurosurgeon with Riverside Hampton Roads Neurosurgical and Spine Specialists here with us today in the studio. Welcome, Dr. McAllister.

William McAllister: Thank you. Nice to be here.

Frankye Myers: Dr McAllister. Briefly talk to me a little bit about why you decided to pursue a career as a neurosurgeon.

William McAllister: Well, uh, you know, there's a lot of different reasons, but fundamentally it was because when I was in medical school, Uh, the things that appealed to me the most were the brain, how it worked, how to fix it when it didn't work, and I just liked neurosurgery from the point of view that it seemed to be one of the last medical specialties where you, once you became a neurosurgeon, you still got to do the full expanse of the specialty. Right? Right. You weren't pigeonholed into doing one thing. Thing the way some specialties go down, it's like these little gaps where they only focus on one specific aspect.

Most neurosurgeons typically can sort of do and operate everywhere on the, on the nervous system, and I like that. I like the mystery of the nervous system. I like the intellectual challenge that dealing with neurosurgical problems presented. But fundamentally I liked working with my hands and fixing things.

Right? And, um, the part of the body that I was the most interested in fixing was the spine in the brain. Right? So

Frankye Myers: interest. That's it. Interesting. So, on this episode, we're gonna be talking about stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of malignant brain and spinal tumors. Talk a little bit about that technology and then the treatment as it relates to those malignant brain and spinal tumors.

William McAllister: Well, in relation to what you asked me first, when I first became a neurosurgeon, I didn't think that this was something that I would be doing. In fact, when I was in medical school, there was really only one place in the United States of America that was doing stereotactic radiosurgery. Uh, but that technology has been embraced by the neurosurgical community at large, and, and we've had it here at Riverside.

And basically, what stereotactic radiosurgery is, Is a way of doing surgery without really cutting on anything. Okay. Using beams and, and arcs of radiation to precisely, uh, treat tumors. Mostly malignant, but sometimes benign, right? That involve the brain and the spinal cord. Uh, through a technique that we have at Riverside.

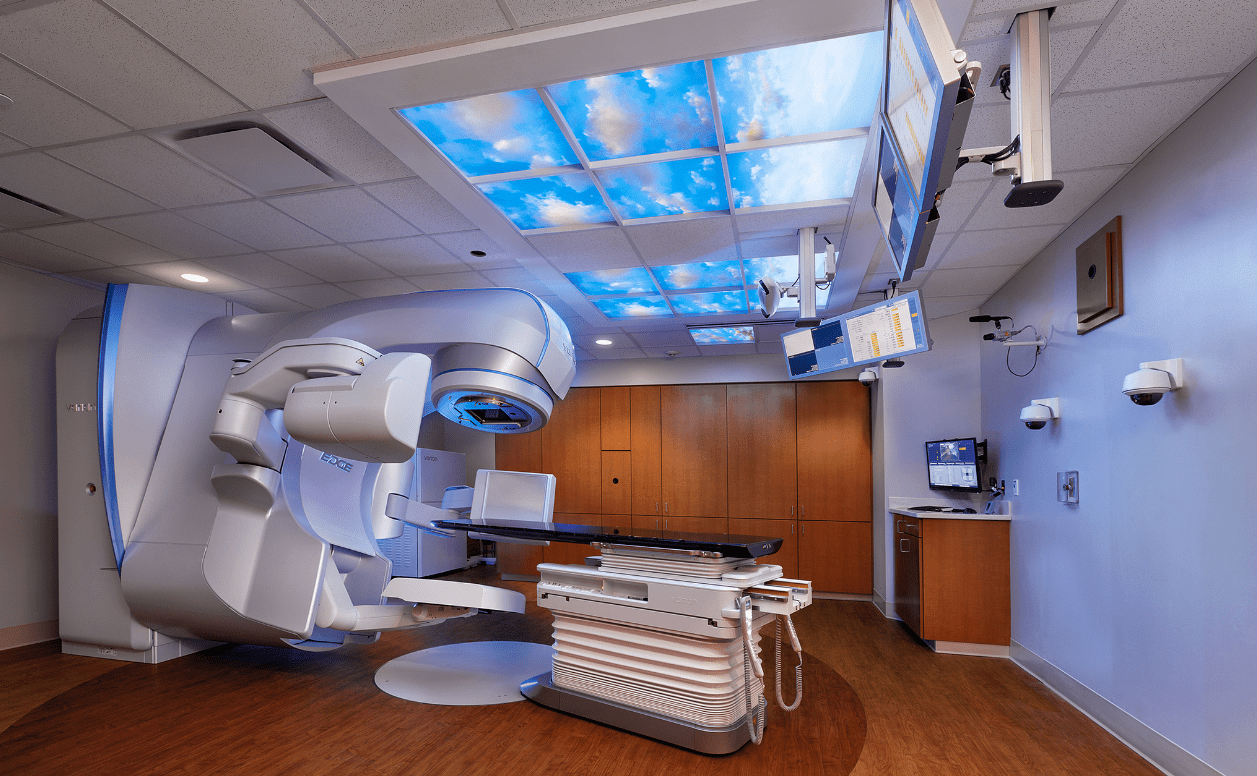

We have one device that's called the Gamma Knife, which has been around since the late sixties and early seventies. It didn't come to North America until 1986 and we got it here at Riverside in 2004, I think. Uh, and then we have another device called the Varian Edge, which we use for the spinal tumors.

Okay, so in lieu of doing conventional radiation treatments and /or doing open surgery, we can now treat many tumors, uh, and I mean many, I mean a lot even, uh, tumors, sometimes people can have up to 14 tumors in their brain. We can treat them with a single session of radiosurgery and achieve the same results.

You would not, that you would operate on someone with 14 tumors, right. You wouldn't, but you can achieve the same result that, like, for instance, doing conventional whole brain radiation, which was the classic way of dealing with something that that might be done, and radiosurgery has offers the precision that you avoid giving radiation to parts of the brain that don't really need it. Right. Fundamentally, that's the difference between stereotactic radiation and conventional radiation. And, um, because the spinal cord is sensitive to radiation and because the brain is sensitive to radiation, you can give what are essentially lethal doses to malignant tumors using stereotactic techniques, uh, and avoid really contaminating the rest of the brain with any unwanted radiation.

So, we've really since about 2005 have treated, the primary malignant brain tumor we treat are brain metastases, right? And in this community, the most common cause of that is lung cancer that has spread or metastasized the brain. But we also take care of patients who've had breast cancer with metastases, melanoma, or skin cancers.

We treated a lady, uh, earlier this week who had a gastric tumor that had spread to her brain. She had five tumors. And rather than doing regular radiation, which wouldn't have worked particularly well for the kind of tumor, we did, we did this procedure called Gamma Knife. And that better than 97, 98% of the time that will work to eradicate these tumors.

Wow. At that's at little to no neurologic costs to the patients. So, it's so they don't develop weakness, they don't develop seizures, they don't have a cut. They don't lose weight. Uh, and so it's, it's, um, it's pretty, it's pretty sophisticated. It's very effective and we have, in large part transitioned from the conventional, the way I was trained when I was in residency to deal with this, right, which was sometimes surgery, sometimes what was called whole brain radiation, um, to doing primarily stereotactic radiation with these.

And, and we've had great results, um, in terms of stopping these tumors from growing and giving people their lives back, and then allowing the medical oncology doctors to continue to treat their primary tumor without having to worry about the, the spread of the tumor in their brain. The one unique thing about our brain, is that the blood vessels are protected by what something we refer to as the blood-brain barrier.

And the blood-brain barrier protects our brain from exposure to any toxins that might get in our bloodstream, but it also keeps medicines from penetrating into brain tissue. So, for instance, if you've got a lung cancer that you want to treat with either chemotherapy or immunotherapy, right? That might work well for the tumor in the lung, or even it spread somewhere else in the outside of the lung.

Say for instance, the bones or the liver. But it doesn't really penetrate as well into the brain. So those medicines typically don't have the same impact on tumors in the brain as they do elsewhere. So, if you can get a tumor to shrink with immunotherapy, say for instance a lung tumor, the same medicine's not going to do that much to it when it's the brain.

So, we, we will supplement the patient's treatment with stereotactic radiation and that. Like I said, works, I would guess it works better than 98% of the time to eradicate these tumors. So, it's a combined approach. You can't just do radiation; you can't just do stereotactic radiation. You can't just do chemotherapy.

You oftentimes have to do the two together in concert with one another. But it has been very effective. And like I said, we've had, uh, a couple, the, the gamma knife technology keeps getting updated, uh, and we will update our device, uh, within the next year, I believe. Uh, we currently have something called the Gamma Knife Icon Unit.

We're gonna update it again. Uh, that technology key, it's fundamentally, it's the same machine it's been since the sixties, but with computer technology, with imaging technology, certain parts of it get a lot safer and a lot faster, right? So, uh, we've, we've, fortunate enough, we keep getting all the newest updates.

Uh, and we'll update it again and, and, you know, so we'll continue to be able to offer this treatment to the patients in our, in our community when they do unfortunately have these types of, uh, brain problems.

Frankye Myers: That, that, that's, that's awesome. And, you know, thank you for your expertise and um, that information for our viewers.

Are there any major, and I'm sure there are probably a lot of them, um, and we probably can't get into all of that, um, in this podcast, but are there exclusions? Are there people that this, this, this, uh, treatment approach would not be appropriate for?

William McAllister: There are, um, size is one factor. Okay? One of the, uh, unfortunate side effect, one of the unfortunate realities when you're dealing with the physics of radiation is that if a tumor gets to a certain volume, meaning that it's the overall size of it gets to a certain point, then the, not that the accuracy is diminished, but the drop off, meaning that the difference between the dose of radiation you're giving at the margin of the tumor to what the surrounding brain tissue is getting, it starts to become dangerous.

Okay? So generally, tumors. With our new unit, we can treat tumors that are up to 3.5 centimeters or about an inch and a half across. Um, beyond that, you get, you start to run the risk that you're gonna cause radiation-induced toxicity. So, for those larger tumors, either, one, you have to do whole brain radiation, which sometimes works and sometimes doesn't.

If the patients in good enough quality and the tumors in a place that's easily accessible, sometimes you can take those tumors out, right? And by debulking them, you can cause them to collapse, and you can, you can create a smaller overall volume to treat. And then the other treatment that unfortunately gamma knife, in terms of effectiveness, gamma knife, still doesn't have, we're not, still, don't have the answer for our, what are called primary malignant brain tumors, which aren't as common as metastatic tumors. But they're the gliomas, and glioblastoma multiformes, right, right. Uh, oliogengliomas. And we, there are instances where we use gamma knife in those tumors, but it's usually as a fallback procedure when other, more conventional, more accepted treatments have failed.

Right. Um, so for instance, if you're diagnosed with malignant primary tumor, the most common of which is being a GBM, not a very good diagnosis to get in terms of how well we do treating it. It's one of the most embarrassing things about being a neurosurgeon is that there's this one tumor that we've all known about since, you know, neurosurgery came into existence, and yet our treatment options and what we offer for it hasn't dramatically improved with one exception, really since the whole age of neurosurgical treatments. Right. So unfortunately, radiosurgery, which was thought that might be able to do something positive for gliomas, hasn't really had much of an impact on the overall, you know, arc of how those patients perform with their tumors.

There's, there are instances where we do treatments, uh, they're, they're, you know, long, there are a couple of patients who are long-term survivors and they do get recurrence that's easily defined and can be easily seen on an MRI scan that doesn't seem to have this kind of spiderweb distribution. Right?

And on those patients, sometimes we can effectively control recurrence, but unfortunately that's a, that's a minority of those patients. Um, so. Um, that's the one place that, and the overall size. So, so if someone comes in with a really, really large tumor that's, say for instance, spread from another tumor elsewhere in the body, , If it's beyond about four centimeters in size, three and a half centimeters, you generally are gonna either have to take that out, uh, or, or, or not do anything. The gamma knife just won't work. So, there is, there is an advantage in gamma knife to catching the tumors early. And, fortunately, our medical oncologists know this, right?

And so they tend to be very, um, alert and scan people at the first sign that there's some reason right to think that they might have a tumor. So, most of the tumors nowadays, because of the way MRI imaging is so sensitive, are caught before that happens. Right. Not all of them. So, but, but the majority, yeah.

So, the early detection, like with all cancer is critical. Uh, and that certainly seems to be, that's true for Gamma Knife, and I, but our, but like I said, our medical oncologists who are usually the primary, you know, physicians and caregivers in charge of these, these patients, of course, yeah, the referrals for us, they're, they're, they're, they're, they're pretty proactive about doing these scans at the first sign. Good. Good. That something, uh, is amiss with the patient, particularly if they're having headaches or some weakness, something that just doesn't seem quite right that makes them suspect that a brain process may be underway.

Absolutely.

Frankye Myers: I, I think for our viewers that just reiterates the importance of preventative care. Yeah. Like having a relationship with your primary care physician, having those annual checkups, um, so that if things come up that you identify them early and really being in tune with your body. And identify 'em when something doesn't feel right, or something is different.

That's really great information.

William McAllister: Yeah, absolutely. Vigilance is, is important in catching things early, like with, I mean, that's why they just changed the breast cancer screening recommendations to age 40. Yes. The, the notion is that if you can catch these things earlier, you've got a much better chance of, of cure and or at least putting things into remission for much longer periods of time.

Absolutely. Um, there is a volume consideration with cancer and once you get too much of it in your body, whether it be your brain or elsewhere, the, the treatments lose their impact. So. Absolutely. Yeah. Absolutely. Getting, getting things diagnosed early is, is, is the best way to go. Yes. For obvious reasons.

Frankye Myers: I think they've done that with colonoscopies as well. Absolutely. Yeah. Kind of shaved off some of those Right. The timeframe in which you, they're covered. Absolutely. Great, great, great information, Dr. McAllister. Thank you. Um, what, what frequently, um, are use treatments for, and you talked a little bit about the malignant, um, the treatment for malignant brain and spine tumors, are there other treatment modalities, um, that you think would come into play?

William McAllister: Um, you mean other things that we treat at the Gamma Knife Center? Yes. Oh, absolutely. We treat, um, so the other things that we treat that we see a lot of are benign tumors. There are a lot of benign tumors in the brain. The tumors common are, are schwannomas, which are tumors that grow on the lining of the nerves.

The most common would be the nerves that control, hearing, and balance. So what are called vestibular schwannomas, which are usually detected when they're small because they typically present with hearing loss. Okay. And people, uh, come in with one hearing ear less, more deaf than the other. Right. And they get a scan and sure enough they've got a small little eight- or nine-millimeter, uh, schwannoma, which usually isn't a life-threatening tumor. You can remove them with surgery, right? Most people will lose their hearing if you remove in surgery. But vast majority of schwannomas, if you treat them with stereotactic radiation will stop growing and shrink. And there's some data to suggest that the hearing preservation is longer.

They still do oftentimes lose their hearing, but you can spare the patient the risk of a craniotomy. There's another type of benign tumor in the brain called a meningioma. Okay. Uh, which can be benign. Most are benign. There's some that are intermediate, some are malignant, but the benign ones can, can, oftentimes, if they're small enough and thought to be some, some don't actually need to be treated.

Okay. Some are discovered in older patients, and they're incidentally discovered, and they won't actually grow. But if there's a sense that they're growing and there's a sense that there's something there that could cause a problem down the road. Those can be treated quite effectively with radiosurgery.

Sometimes meningiomas are in places where you can’t take them out. You can't fully remove them. They're attached to nerves. They can be attached to blood vessels. So sometimes you'll do an operation on a meningioma, but you'll deliberately leave something behind because you know, if you're too aggressive, you might cause some harm.

So you can go back after a surgery and, and touch it up with gamma knife. Right? And that will oftentimes prevent regrowth. There's a condition that is totally unrelated to a tumor called trigeminal neuralgia, which is a facial pain syndrome, that most patients will tell you is, in people that treat it, which I'm one of will say, it's probably the most painful thing anyone can experience. Um, and in fact, prior to the advent of therapies for the most common way people dealt with it was that they committed suicide cause the pain was so extraordinary. And that actually can be sometimes treated quite well with radiosurgery by radiating the nerve that controls this.

It's called the trigeminal nerve. And uh, that's one thing that we often will treat, particularly in older patients who don't want to undergo more invasive procedures. Uh, radiosurgery to the fifth cranial nerve can be an effective remedy for that. In fact, that's one of the reasons radiosurgeries was actually invented by this inventor, the guy named Lars Leksell, who's long since passed.

But he was interested in figuring out a way to treat trigema neuralgia for the patients back in the sixties where in his home in Sweden, who didn't have really good options. And then there's a brain blood vessel condition called AVMs, arteriovenous malformations, which can bleed. They're not tumors, but they're not normal blood vessels.

So, they have some component of what we call neoplasia. They're abnormalities, aabnormalities of the blood vessels. Um, and they actually can be treated with radiosurgery. You can define them the same way you define a tumor, although they've got blood flow through them, right? Right. And, and the abnormality is just that the blood vessels are abnormal, but if they're small enough again size is important.

Um, if you treat 'em with radiosurgery, within two years, about 85 to 90% of them will obliterate and will go away. And therefore, the risk of of, of bleeding goes down. And that's a real advantage, that's a real help. Cause some of these can be very deep in the brain. Right? Right. Uh, they can present with bleeding, they can be very problematic.

And getting them can be challenging because one, they bleed a lot when you operate on them, and particularly if they're deep in the brain, it's very challenging to do that without causing harm to the patient. Right. So radiosurgery is a great option for small, deep seeded AVMs that are in what we call eloquent parts of the brain.

So we treat all of those things right. Um, probably the most common thing we treat though, is what we initially mentioned, which is the malignant metastatic brain tumors. That's by far and away our most common diagnosis, but we treat a fair bit of all the other things as well.

Frankye Myers: Okay. Okay. Is there a family history associated with some of these tumors? Is there genetic testing that can identify these things?

William McAllister: There's a rare condition that can -, meningiomas can run in families. There's a condition for, uh, vestibular schwannomas called neurofibromatosis two. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Which has, uh, a history which is genetic, but the vast majority of things that we treat in neurosurgery, whether it be meningiomas, gliomas, all those things. They’re, , it's not as genetically linked to some other issues in health, like for instance, diabetes. Right. And high blood pressure. Right. Most of the things that we deal with in the neurosurgical world, um, are not, at least as we, as the current state of medical knowledge, we don't think they're genetically linked.

Frankye Myers: Okay. You talked a little bit about the, um, stereotactic radiology, uh, procedure. Can you just kind of walk it out step by step? What would that phase looklook like for someone?

William McAllister: So, I can tell you, like for instance, tomorrow we're treating a lady who has known lung cancer. And she's actually had previous gamma knife before.

. And we just did a routine follow up MRI scan on her to check our work, which we do pretty much in the first year, every three months after we've done a treatment. Mm-hmm. And so, because she had her MRI down at Riverside, they know that we may retreat her. Okay. And so, they do a special type of MRI protocol that allows us to create a model on the computer in our, in our Gamma Knife Center or the Radiosurgery Center. And she, in fact, had an MRI early in the week. Okay. And she was found to have a few new tumors. They were all quite small. Mm-hmm. None of - the biggest one was, I want to say, six millimeters across.

Mm-hmm. So, she had no symptoms. Mm-hmm. But she, she has these new tumors. So basically, what happened was she lives up near Richmond. But I called her. She didn't wanna drive down. I called her. She had seen her report on the iCare, the MyChart app. So, she was nervous. She knew that it showed that one, the tumors we treated were gone. But the radiologist noted that she had several new tumors. So I called her and I said, you know, how do you wanna deal with this? She's young. She's like, I'm still in the fight. I still, I don't want to give up. So basically, we were able to take her MRI scan that was done already, imported into our gamma plan software.

We've already planned her treatment. She will come down tomorrow morning to the radiosurgery center early in the morning. She'll probably get there at six in the morning. Around 6:30 in the morning anesthesia and I will meet with her, and we will give her sedation and kind of put her into a twilight type of sedation,

similar to like you would get for colonoscopy. And then we'll put this frame on her skull.. The pins go into your skull, but you're numbed up so you don't feel it, and you're given medicine, you don't remember it. And then she'll get a CAT scan in the MRI -in the gamma knife center, excuse me.

That CAT scan will then meet with the computer program will merge to the previous MRI scan that showed the tumors. And then once we get the two to merge, myself, The medical physicist whose name in this instance happens to be Martin Richardson. Right, the radiation oncologist who will determine how much radiation we're giving all these tumors.

Right, right. We all have to sign off. We all have to review what we've looked at, how we planned it, make sure that the radiation isn't touching the nerves that go to her eyes, her brainstem, to any significant degree. We'll sign off on it. She'll then go, the frame will stay on. Cause in the gamma knife there's a thing that locks her into the frame.

And the way the ga Yeah, the way she moves. Okay. Because the way the gamma knife works is the radiation always comes to a single point. We can change the shape of the radiation, but every time it turns on and the radiation comes out, it's always comes the point. That point. And what happens in the frame is we move her.

So the tumors then are put in where the gamma knife's gonna open. So, she's on a table that moves through a set of XYZ coordinates and the tumor, every time she hits the spot, the table moves, the, the radiation sources open up for the set amount of time it takes to deliver the dose. She sits there, and then as soon as that hits the, the, the apertures that close the radiation sources off from the rest of the world close, we move her to the next spot.

We open it up, amazing. We open again, and she just sits there, and she'll move however many times we've decided we need to do the treatment. And that's, that's how it'll be done. And then once she's done, we'll take the frame off, she'll go home. Right. And in about three months we'll get another scan and make sure that it looks like everything went away and looks good.

Frankye Myers: So, no hospitalization requirement? No, no. It's all outpatient. That is, that is phenomenal. Excuse me. Yeah. That's amazing.

William McAllister: Yeah, it's amazing. Yeah. It's, it's a, it's a, it's a big improvement over what we used to do. Absolutely.

Frankye Myers: Um, is there anything else that you can think of, and if someone is listening or knows someone who, um, is newly diagnosed, you know, sometimes a second opinion is, is is good to have, they may have heard about this technology for the first time listening to the, this podcast.

How could they connect with you, uh, and someone, um,

William McAllister: in your, and just either call the the Riverside Radiosurgery Center. Uh, which is 534-5220. Okay. Call my office. Um, and, you know, we can set up a follow-up appointment. We can also do, if patients have imaging on discs, you know, they can mail their discs to the office.

Okay. Right. If they were done within the Riverside system, we can just pull the MRIs up as long as we have permission to do so, and we can review their studies and do either phone visits or video visits or in-person visits and discuss with them whether they're a candidate for the uh, radiosurgical technology.

Frankye Myers: I gotta ask you something cuz I told somebody I would ask you. They ended up having Bells Palsy. Can you, can you talk a little bit about what causes that? Sometimes people think they, they have some sort of major tumor going on because of the facial drooping.

William McAllister: Right. So, Bell's Palsy is a very dramatic presentation where one side of your face goes completely weak, and you look like you've had a stroke.

Right? But the cardinal feature of Bell's Palsy, that it’s, it's just facial weakness. Uh, you, you can't close your eye, right? You can't smile. You have a hard time swallowing, and it's rather abrupt in onset, and there's no other neurologic deficit. There's generally no pain with it, okay? Sometimes people get a little ringing in their ear.

It is actually currently thought that it is a viral infection, okay? In fact, most of the time you're put on the same medicine that people take for zoster, okay? It's thoughts to be so, to be a a, a, a, a herpes-like-virus. Okay? Not the virus. Okay. But that reactivating in what's called the geniculate ganglion of your seventh cranial nerve.

So, it's not something we treat with radiosurgery. Right, right, right. But it is rather dramatic. It looks like a stroke. Right. And nowadays in our, our era of being hypervigilant about stroke, I think most people wake up and they see that, and they look at someone and they think, oh, it's a stroke. Right. But it is not a stroke.

It usually can be diagnosed by the fact that the patient doesn't have any other neurologic - so they have no arm weakness on that side. They have no numbness. Um, and usually it does get better. Okay. Um, there are a small group of people that never get full facial function back, but the vast majority of people, do improve over time.

Okay.

Frankye Myers: Thank you. Yeah. Thank you so much for taking time outta your busy schedule. You're welcome. And talk with us. Thank you for having me. Lot. Great information. You're always welcome to come back and talk with us on Healthy You Podcast. All right. You're welcome. Thank you so much.

William McAllister: You're welcome. Thanks a lot.

Frankye Myers: Thank you for listening to this episode of Healthy You. We're so glad you were able to join us today and learn more about this topic. If you would like to explore more, go to riversideonline.com.