As part of her daily routine at Riverside Regional Medical Center, Mary Pancoast reviews the list of patients scheduled for upcoming surgical procedures.

Her heart nearly stopped one day when she saw these words on the next morning’s log: “Allan R. Carpenter, age 82.”

During the Vietnam War, like many teenagers, Pancoast supported the troops by wearing a stainless steel bracelet inscribed with the name of a soldier who was a prisoner of war. The name on her bracelet matched the one right before her eyes. A patient from Mathews County, Allan R. Carpenter, was scheduled for back surgery on Sept. 4, 2020.

Could it be?

“Oh, my gosh! This could be him!” thought Pancoast, in her 28th year working at Riverside.

Navy Cmdr. Allan Russell Carpenter was interned as a POW after he ejected when his aircraft was hit by artillery fire on Nov. 1, 1966. The fighter pilot landed in the water. Fractured and bleeding, he stared down a machine gun held by a North Vietnamese soldier. He wondered whether he would feel the bullets when they hit him.

Instead, he was captured, sent away to the notorious prison camp known as the “Hanoi Hilton.” For six years and four months, minus a few photos, he didn’t see his wife, Carolyn, or their four children, all under 7 years of age.

Meanwhile, Pancoast, a high school junior in northern New Jersey, never removed the bracelet — purchased for $10 — from her left wrist.

“I wore it in the shower, at gym in school, in the garden outside working in the yard. I never took it off,” she says. “You were supposed to wear it until you heard about the fate of the solider you were remembering.”

On March 4, 1973, Carpenter was released. Pancoast learned the news from the now-defunct Village Voice, the New York City-based alternative newsweekly where she first learned about the bracelets. Scanning 555 names of released POWs, she found his: Allan R. Carpenter.

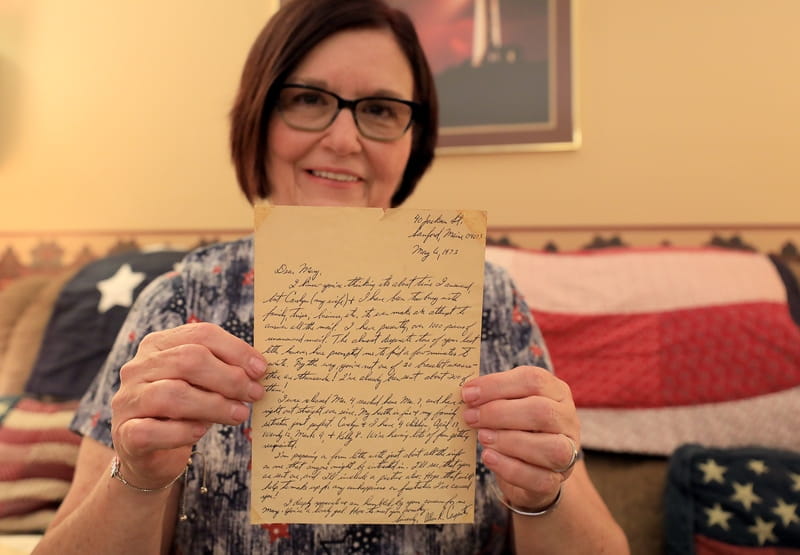

Forty-seven years later, standing inside Riverside Regional Medical Center, she was stunned to see that same name. Just a few weeks earlier, in an attempt to organize, she thumbed through old scrapbooks. She reread a special letter of gratitude from Carpenter sent after he returned home.

Carpenter mailed form letters to everyone who reached out to him, many of whom included their bracelets with his name. Pancoast wrote multiple times, so he responded to her personally.

He closed his letter written 47 years ago by mentioning the possibility of leaving his New England home to move to Norfolk, Virginia. “I hope we meet someday,” he wrote.

Pancoast never planned to live in Virginia. She had actually hoped to be an Army nurse, but after she married, she relocated several times due to her husband’s job. She settled in Newport News for good 35 years ago.

That “someday” Carpenter mentioned turned out to be on Sept. 4.

Knocking at Carpenter’s hospital room door, Pancoast peeked in. She blurted the only words she could find.

“This is going to sound crazy, but I’m just going to say it. Are you Lt. Cmdr. Allan R Carpenter?”

“Yes, ma’am, I am,” he responded, surprised.

Pancoast nearly fainted. She revealed that she had worn his name on a bracelet all those years ago. He didn’t remember her by name but encouraged her to chat with him and his wife.

“I haven’t met one of my bracelet wearers in almost 15 years,” he said pridefully. “Can I take your picture?”

That nearly floored Pancoast. “Can I take your picture?” she asked.

“I was absolutely delighted to meet her,” says Carpenter, retired at Cobbs Creek in Mathews County, just 54 minutes from Pancoast’s home in the Glendale section of Newport News. He’s lived in Hampton Roads since 1979.

“Mary, I just appreciate every day,” Carpenter said during their exchange. “When I get up, I go downstairs, I open my front door and I walk out of it.”

For those six years as a POW, the door was locked. Carpenter doesn’t take for granted his ability to do that today or any day.

Pancoast regards the chance meeting as “glorious and amazing. It’s something I will never forget. Like the letter I got from him 47 years ago. I will never forget that. And I will never forget this.”

Today the Carpenters enjoys a quiet life near their children, nine grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Humble about his sacrifice, he calls the true heroes the soldiers who lost their lives for their country.

Carpenter served for 23 years and received three Silver Stars for valor in combat.

“As you get older, you reflect on some of the basic truths of life, what matters and what doesn’t,” he says. “Whether you have the latest sneakers or cell phone or computer is not really important. What’s important is relationships, who you are, who your loved ones are and how they’re handling things.

“Veterans Day wraps that all up for me. My service family is extended. I’ve got a lot of friends, and it brings together all the sacrifices and the losses and the absolutely wonderful stories of people.”

Pancoast takes a few moments every Veterans Day to reflect on its significance. Beyond wearing the bracelet, Pancoast never forgets to honor service members. Her house is literally red, white and blue. Her husband, Bob, has learned to be patient if they’re walking through an airport. If she spots a group of service members, she thanks each one individually.

Pancoast still has the bracelet that bears Carpenter’s name. It’s never left the jewelry box on her dresser.

“It’s nicked up a bit from all the wear, but it’s still there,” she says. “I haven’t worn it a lot as a 65-year-old, but I’ll never part with it.”